- Norwich Blogs

- Blogs

- Russia Hedging Its Bets in the Red Sea (Part One)

Russia Hedging Its Bets in the Red Sea (Part One)

By Richard Moss

Disclaimer: These opinion pieces represent the authors’ personal views, and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Norwich University or PAWC.

PART ONE: Service Support Centers (aka Basing)

Disclaimer: This opinion piece reflects the author’s personal views and does not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense or of its components. The author thanks Professor William Murray, Mr. Christopher Fernandes, and Ms. Anna Davis for their feedback.

These opinion pieces represent the authors’ personal views and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Norwich University or PAWC.

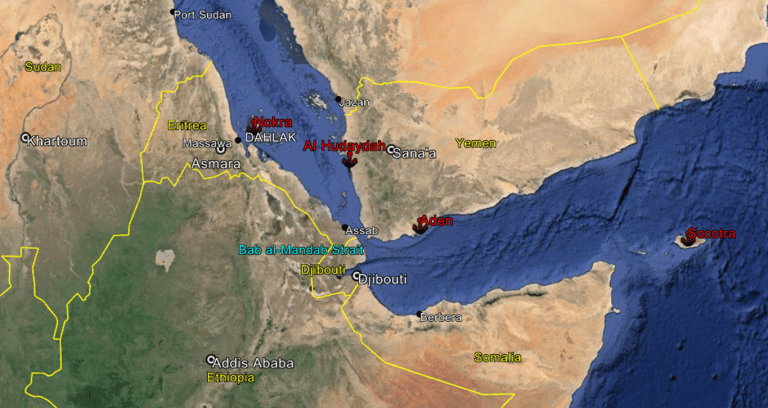

Since October 2023, the Houthis in Yemen have launched drones, anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), and ballistic missiles against Israel and international merchant ships around the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, a strategic waterway between the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. Ostensibly, the Iran-backed Houthis—a group the U.S. has once again labeled a terrorist group—has launched their attacks against Israel and its supporters in solidarity with the Palestinians after Hamas’ attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, and Tel Aviv’s subsequent operation against Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

The reality is that Houthi attacks have struck commercial vessels indiscriminately, including ships carrying cargo or owned by countries without any apparent links to Israel. U.S. and allied naval combatants dispatched to the region have shot down dozens of Houthi drones and missiles, but several Houthi attacks have hit merchant ships, such as a vessel carrying Russian naphtha in January 2024 (Another ship carrying Russian petroleum was reportedly targeted, but the Houthis narrowly missed it). In addition, U.S. and allied forces have repeatedly struck Houthi targets to protect international shipping. Nevertheless, insurance rates have increased and commercial carriers, such as Maersk Lines, have suspended Red Sea transits by diverting around Africa via the Cape of Good Hope. Egypt’s revenues for the Suez Canal, which connects the Red Sea and the Mediterranean, have plummeted 40% to 50%.

Aside from statements decrying U.S. and UK strikes against the Houthis as an “irresponsible adventure that risked sowing chaos across the entire Middle East,” and as “illegal” without a mandate from the United Nations, Russia has largely avoided the spotlight. (Moscow evidently would like observers to overlook its hypocrisy with its nearly universally condemned, illegal war against Ukraine.) Moreover, with legal and illicit income from hydrocarbon shipments supporting Moscow’s war, Russia continues shipments via the Red Sea.

This article is divided into two parts. The first part explores how Russia is looking to expand basing to the Red Sea, regardless of unrest in the region. The second part shows how Moscow is hedging its bets on the Red Sea by pursuing alternative maritime routes favorable to Moscow over the longer term.

To Syria…and Beyond?

Russia has used its intervention in Syria since 2015 as a foundation to expand Moscow’s maritime interests in the Mediterranean and the Middle East. First, Moscow and Damascus signed a 49-year lease for the port of Tartus, giving Moscow a ‘service support center’—really a naval base—to support a permanent naval presence in the Mediterranean. Russia’s 2022 Maritime Doctrine reflected Moscow’s revised approach to the Middle East, North Africa, and beyond as a result of its Syria intervention. In contrast to the 2015 Maritime Doctrine, the 2022 Maritime Doctrine directly called for strengthening and building beyond Russia’s partnership with Damascus into the Mediterranean basin and developing relations with states in the Red Sea and the Middle East region.

Moscow attempted to build off its momentum from the Syria intervention to negotiate the establishment of another ‘service support center’ in Sudan at Port Sudan on the Red Sea with the former longtime dictator Omar al-Bashir. Moscow and Khartoum began negotiations in 2017, but a military coup d’état overthrew Bashir following popular protests in 2019. A transitional military government signed the agreement to set up a service support center in July 2019, and Russia announced in late 2020 that it had also signed the agreement. The Russian-language text of the official agreement was posted on the Russian government’s legal information internet portal (pravo.gov.ru) in December 2020, with the Russian, Arabic, and English versions published on the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs website in April 2021. The agreement specified that Sudan would transfer land plots and their adjacent water spaces, free of charge, to Russia, and that Moscow would develop and improve the facilities and help develop the Sudanese Navy.

Colonel-General Alexander Fomin, a Russian Deputy Minister of Defense, explained Russia’s “need” for a base in the Red Sea to Krasnaya Zvezda, a newspaper for the Russian military, in 2020:

We are interested in a military presence in the region. First, to combat terrorism, piracy, smuggling of weapons, drugs, and the slave trade, as well as to ensure safe commercial shipping. The opening of a logistic support point in Sudan will allow the Navy to create conditions for safe maritime activities not only for Russia but also for other states. This point will enable ships to stay in the far ocean zone and participate in military, peacekeeping, and humanitarian actions. Also, the implementation of this project will create favorable conditions for providing ships and vessels of the Navy that are in combat service and make inter-naval crossings through the Red Sea.

Despite Russia’s announcements about the facility and publishing of the agreement, instability in Sudan has repeatedly delayed its implementation. The military government has suffered infighting with violent flareups, and another military coup in 2021 overthrew the transitional civilian prime minister, Abdalla Hamdok. In February 2023, the military junta in Khartoum finally approved the possibly revised plan for the Port Sudan base—apparently after getting Moscow to sweeten the deal with weapons and goods—but a final agreement cannot take force until an as-yet-to-be-formed Sudanese legislature ratifies the agreement. Armed conflict between rival military factions in April 2023 may have shelved the deal more permanently.

Soviet Naval Bases in the Red Sea region during the Cold War.

History doesn’t repeat, but it may rhyme.

With the instability in Sudan, several sources have claimed that Moscow is pursuing an agreement with Eritrean dictator Isaias Afwerki to set up a base in Massawa or the Dahlak Islands. The Russian Navy’s port call to Eritrea by a Pacific Fleet frigate, Marshal Shaposhnikov, and the visit of the deputy commander-in-chief of the Russian Navy, Admiral Vladimir Kasatonov, certainly reinforces the perception that Moscow is looking to bolster ties to Asmara. Moscow may be pursuing parallel ties with Eritrea and Sudan, or it may be trying to play Asmara and Khartoum off each other.

Russia is no stranger to the area and history may be a cautionary guide. The Soviet Union established a naval support base at Nokra on the Dahlak Islands, which was then part of Ethiopia, during the late 1970s. Moscow increased ties with the so-called Derg regime that overthrew Haile Selassie in 1974 and came to see Ethiopia’s eventual military ruler, Mengistu Haile-Mariam, as a socialist in the Soviet mold. According to historian Odd Arne Westad, by 1979 the Soviet bloc sent more than seven thousand civilian and military advisers to Ethiopia and Moscow sent “the single largest foreign assistance program the Soviets ever undertook after China in the 1950s” (Westad, Global Cold War, p.279).

If the Russian move back to Nokra is true, it would be a historical irony, as Soviet forces abandoned the naval support base in 1991 under shelling for months from the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF), led at the time by the same Isaias Afwerki. The Soviet base and convoys came under fire because the EPLF was targeting the Ethiopian naval base near Nokra, Soviet ships were delivering aid to the Ethiopian Navy, and Ethiopian ships often attached themselves to Soviet convoys, according to Rear Admiral V.N. Burtsev (retired), who served as the commander of Soviet surface forces stationed at Nokra. The EPLF’s successful campaign against the city of Massawa, the Dahlak Islands, and the capital city, Asmara, eventually resulted in an independent Eritrea. O. Semenov, who served in Ethiopia aboard a Soviet Pacific Fleet workshop ship that came under fire, noted with some bitterness that Soviet sailors who served in Nokra on ships outside the Black Sea Fleet were not recognized as combat veterans until 2018-2019.

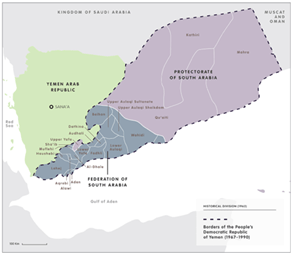

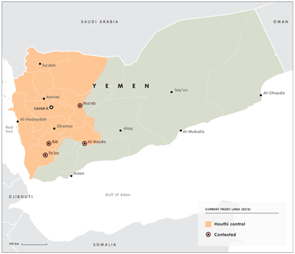

The Soviet Union also had bases in the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) at Al Hudaydah and in the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen) at Aden and Socotra during the Cold War. Some of the Soviet ships that fled Nokra went to Aden. The areas the Houthis presently control roughly overlap with the area that was North Yemen until 1990.

The historical borders of the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen) on the left. The Houthi-controlled parts of Yemen on the right. Maps from the European Council on Foreign Relations

No exit from the Red Sea

According to the Russian business newspaper, Kommersant, 8 to 10 percent of Russia’s foreign trade goes through the Suez Canal. Although the article does not specify if the “small volumes” are based on tonnage or value, it concedes that 2.5 million to 3 million barrels of Russian oil go through the Suez Canal each day, with India as the largest buyer.

In addition, the trade flows affect Russian Baltic and Black Sea ports. Igor Yushkov, a leading expert of the Russian National Energy Security Fund, told Kommersant, “Almost everything that is loaded in Novorossiysk [in the Black Sea] and in the Baltic Sea, in the ports of Ust-Luga and Primorsk, actually goes through the Suez Canal, the Red Sea and further past Yemen.”

As Nikita Smagin of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace points out, “If the Suez Canal were closed, Russia would be forced to send its tankers all the way around Africa to reach India. Its fleet of tankers is not big enough to maintain current export volumes if that were to happen, and sourcing more would be no mean feat: tanker demand would be sky-high in such a scenario since Russia is not the only country transporting oil through the Suez Canal.”

Although Russia’s experience in the Red Sea recalls some bitter memories, the bottom line is that Moscow still relies on the route for trade, and for influence in Africa and the Middle East. The Russians have been very clear about the importance of geostrategic chokepoints in their maritime and naval doctrines, and the Red Sea remains one location where Moscow has attempted to meet its aspirations by establishing logistics facilities for the Russian Navy and commerce. Ultimately, Moscow appears to be making a virtue of necessity by filling its coffers from its oil sales via the Red Sea, aligning with Iran, and promoting an anti-western, pro-authoritarian message in Africa and the Middle East.

Richard A. Moss, Ph.D. is an associate professor in the Russian Maritime Studies Institute at the U.S. Naval War College's Center for Naval Warfare Studies. He serves as the technical director of the Holloway Advanced Research Program and is writing on a short history of the post-Soviet Russian Navy with CDR Ryan Vest. Professor Moss also specializes in U.S.-Soviet relations during the Cold War and is an expert on the Nixon presidential recordings. He previously served as a government and contract military capabilities analyst with the Department of Defense and as an historian with the Department of State. The University Press of Kentucky published his book, Nixon's Back Channel to Moscow: Confidential Diplomacy and Détente, in 2017. Dr. Moss earned a Ph.D. and M.Phil. in History from George Washington University and a BA in History from the University of California Santa Barbara.