- Norwich Blogs

- Blogs

- On Battles Lost and Things That Endure

On Battles Lost and Things That Endure

Disclaimer: These opinion pieces represent the authors’ personal views, and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Norwich University or PAWC.

During the summer of 2021, I was travelling to see old friends and make up for time lost to COVID when it became clear that a disaster was unfolding 7,000 miles away. Somewhere on the interstate as I scanned from one NPR station to the next, I had to face the fact that the cause I had devoted years of my life to was unraveling, and that Afghanistan would again come under Taliban control.

It had been years since I had any significant involvement with the Afghanistan war, but that experience had been deeply formative for me, as it had been for many of my generation of post-9/11 veterans. No one ever teaches you how to cope with losing a war, but we all had to reckon with the meaning of America’s first unambiguous defeat in our lifetime.

I had been a teenager on 9/11, and then spent my college years watching in frustration as the U.S. effort in Iraq seemed to go off the rails. By contrast, the war in Afghanistan, while never fully resolved, seemed to offer a reasonable chance of success and an unambiguously worthy cause. This was a time when leaders still spoke seriously about an “end game” after which the government in Kabul would be able to assume responsibility for its own security. From age 24 to 27, I served as a mission coordinator supporting MQ-1B remotely piloted aircraft. Working with RPAs (“drones”) places you in a strange relationship to combat, deeply engaged with events on the ground from the safety of a facility back in the U.S. I have personally never set foot in Central Asia, but I can still describe Afghanistan’s geography from memory. I don’t think I ever seriously considered the possibility that we might lose, even though I knew that the odds in Afghanistan were historically against outside military interventions.

After leaving active duty, I continued to believe in the mission, but I couldn’t help but notice the growing sense that our involvement lacked a realistic finish line. I realized that something had changed in my thinking around 2018 when a young friend took an interest in joining the military and it occurred to me that I didn’t want him inheriting a war that our nation didn’t seem all that invested in winning. It wasn’t that the Taliban were winning, but rather that their astonishing fortitude repeatedly confounded American counterinsurgency efforts. Nevertheless, I still agreed with the viewpoint that our presence formed part of a generally successful counterterrorism strategy that had prevented a repeat of 9/11. I had no rebuttal to the critics who increasingly demanded to know when our service members would be coming home, but continuing the mission seemed wise considering that Afghan security forces would certainly collapse without American support. But although some of us might have preferred to maintain a U.S. presence indefinitely, the reality was that after twenty years, the American people we understandably tired of the whole enterprise.

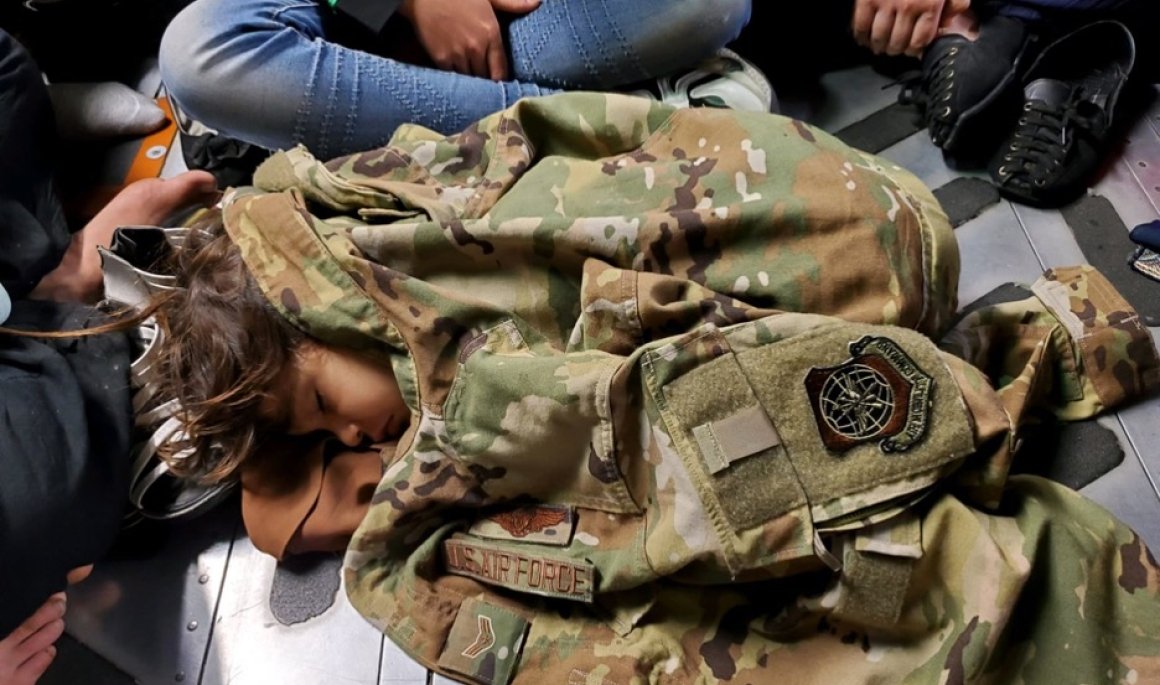

Ultimately, the two major questions were how fast the Taliban would seize control once we left, and whether we’d take care of our allies when they did. In the event, the situation unraveled practically overnight once the pullout started in the summer of 2021. What had been planned as an orderly withdrawal devolved into a frantic evacuation that threatened to leave behind many of the Afghans who had sided with America during the nearly two decades we spent in their country. With other routes cut off, throngs of locals desperate to escape mobbed the Kabul airport. Following events from halfway around the world, veterans like me found we could still take genuine pride in Air Mobility Command (the transport arm of the Air Force), which emerged as the one thing going right when everything else went wrong. In the first chaotic hours of the evacuation, one aircraft managed to depart Kabul with an astonishing 800 passengers aboard, and I doubt there was an Air Force veteran alive when the news broke who didn’t wish they could have been a crewmember on that flight. In the course of 17 days, American and allied aircraft succeeded in transporting 124,334 people out of Kabul.

Around this time, I wrote to a fellow veteran about how much I wished there was something (however small) I could do to help sustain the air bridge coming out of Afghanistan. “I and many of the people I care most about gave the most vibrant years of our lives to try and give regular Afghans a fighting chance against [the Taliban], and now the best we can hope for is that a 21-year-old load master can find a way to cram a few extra souls aboard an overloaded C-17.” Meanwhile, others who had served in-country and formed personal relationships with Afghan translators and allies were working frantically over phone, text, and social media to get their friends out. In an unprecedented crowdsourced rescue operation that came to be described as a “digital Dunkirk,” an ad hoc network of volunteers all over the world guided fleeing Afghans past checkpoints and around obstacles to the airstrip. The airlift ended on August 30 with the departure of the last American flight from Kabul.

Watching the collapse of democratic Afghanistan represented a shared trauma for American’s post-9/11 veteran community; the VA noted a sharp uptick in people contacting their crisis line (although mercifully the feared wave of suicides never materialized). When The Atlantic published a seminal longform account of the evacuation in early 2022, I still found the subject sufficiently emotional that I needed to read it in segments; when I mentioned it to a colleague, he indicated that he wouldn’t read it at all. Another friend of mine would eventually write an essay describing the impact of “mission injury” on an all-volunteer force where the reasonableness of prioritizing military service over a stable family life no longer made sense in light of the loss of Afghanistan. Other observers traced a connection between mission failure and the pronounced reluctance of young Americans to enlist.

But by any measure, the trauma experienced by American veterans was (and is) dwarfed by that of Afghans themselves. Uprooted from their homes, sometimes with little more than the clothes on their back, America’s Afghan allies deserve the warmest welcome and deepest solidarity that our nation can offer. I admit that my position is extreme: if it were up to me, every Afghan who ever so much as gave a cup of cold water to an American would receive a U.S. passport the moment they set foot on our soil. By right, these men and women are already Americans, and our country can only be enriched by the addition of their extraordinary courage and resourcefulness. And like many post-9/11 veterans, I am beyond exasperated that so many of our Afghan friends remain caught in a maze of legal ambiguity and red tape two years on. As a matter of morality, we clearly owe them better; as a matter of national security, America’s global influence would be well served by demonstrating that we are committed to doing right by those who make common cause with us. My personal hope is that Congress will pass Afghan Adjustment Act as a first step toward paying the debt America owes these people – a debt that veterans feel with particular intensity.

For someone to volunteer to serve in our nation’s military is an act of trust in the wisdom of our leaders and the rightness of our cause. However, the outcome of any given war cannot be known in advance, and my generation of veterans is hardly the first to see our efforts come to naught. But even if you can’t always believe in results, you can still believe in your teammates, and although you might start out because of the mission, what keeps you going is the people you meet along the way. When I try to make sense of it all, I think of a message I sent to two close friends as things were falling apart – “[Your] friendship is the best thing that happened to me during my time on active duty. … Anything done alongside the two of you will always be worthwhile.”

About the Author

Robert J. VandenBerg is a sociologist and criminologist specializing in the study of political violence and a senior fellow at the John and Mary Frances Patton Peace and War Center. A veteran of the United States Air Force, Dr. VandenBerg previously served on the faculty at Norwich University, where he oversaw that creation of the academic program in Intelligence and Crime Analysis. The opinions expressed in this essay are the author’s own and do not represent the official position of the United States Government, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Air Force.

Sponsored by the John and Mary Frances Patton Peace & War Center of Norwich University, VPW features subject matter experts and students who present their opinions and arguments on critical issues related to peace and war in the international community. We hope that a chorus of small voices in this forum will help illuminate a world filled with a variety of complex challenges.