- Norwich Blogs

- Blogs

- The America First Trade Policy: The Knowable and Unknowable Consequences

The America First Trade Policy: The Knowable and Unknowable Consequences

By Dan Ciuriak

Disclaimer: These opinion pieces represent the authors’ personal views, and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of Norwich University or PAWC.

President Trump’s “America First Trade Policy” has set in motion a comprehensive review of U.S. trade policies and relations, with a principal focus on “large and persistent merchandise trade deficits”, the exchange rate policies and practices of major trade partners, and the functioning of existing trade agreements, among an overall 14-point review mandate (White House 2025). Most of the responses are due by 1 April 2025.

President Trump has already exercised a campaign promise to impose 25% tariffs and other punitive measures on any country that is not forthcoming in responding to his demands. Colombia was the first target following its refusal to accept US military planes carrying deportees. Across-the-board punitive tariffs were subsequently announced on Canada and Mexico on 1 February, ostensibly to prompt changes to Canada’s and Mexico’s border measures on illicit flows of fentanyl and migrants. In each case, a deal was reached within days to forestall the imposition of tariffs. However, tariff surcharges and other measures for imports from China remain on the books. The threat of tariffs continues to hang over trade with Canada, Mexico, and other partners such as the European Union. More fundamentally, one can hardly ignore the implications of the consideration in the America First Trade Policy of an “External Revenue Service,” aiming to fund a substantially slimmed-down U.S. government on an ongoing basis. This signals a fundamental change in U.S. foreign economic relations and, given the links that have been drawn between economic and security policies, a fundamental change in the latter area as well.

The Anticipated Consequences

We have had several recent natural experiments of the impact of the imposition of new trade barriers –Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum, Section 301 tariffs on China, and the UK’s exit from the European Single Market. [i]

Conventional ex-ante analysis of the Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum predicted increased US production of steel and aluminum but negative impacts on downstream sectors due to higher costs of production inputs.[ii] The outcomes were actually worse.

- Steel and aluminum production did not make gains and jobs were not protected: “The trade war has not to date provided economic help to the US heartland: import tariffs on foreign goods neither raised nor lowered US employment in newly protected sectors; retaliatory tariffs had clear negative employment impacts”.[iii]

- As predicted, higher costs' negative impacts on downstream sectors were significant (Durante 2024). [iv]

- Worse, applications for exclusions to the Section 232 tariffs numbered in the hundreds of thousands in the first years of the policy[v] and continue in the tens of thousands annually. To accomplish these tasks, the implementing US agency has requested, for fiscal year 2025, funding of $223 million to staff 611 positions.[vi]

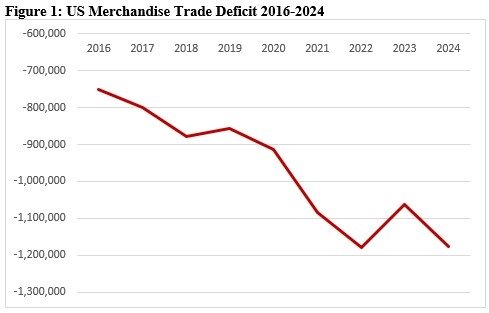

The tariff war launched against China served as a natural experiment in applying tariffs to address a merchandise trade imbalance. It has failed – the U.S. merchandise trade deficit has widened (see Figure 1 below).

It should not pass without noting that the most fundamental theorem of trade policy is Lerner Symmetry[vii] which demonstrates that a tax on imports is equivalent to a tax on exports. That is, even as tariffs serve to reduce imports by making them more expensive, they also work indirectly to undermine a country’s exports (including, for example, by causing the exchange rate to appreciate, making exports more expensive). The failure of the Section 301 tariffs to achieve the rebalancing of trade is thus fully anticipated by trade theory. The actual deterioration of the US external balance goes beyond what theory would suggest and can be attributed to increased government spending and tax cuts that resulted in increased domestic dis-saving and thus increased foreign borrowing. This was partly due to discretionary spending by the first Trump administration, partly due to the very necessary fiscal response to the pandemic, and partly due to the industrial policies adopted by the Biden Administration to capture the lead in new general purpose technologies.

As for Brexit, the litany of economic woes is long and sobering, notwithstanding the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) that was implemented following the UK’s exit from the Single Market. A particularly compelling approach to evaluating the marginal impact of Brexit on the UK is to compare actual UK performance to a constructed doppelgänger UK economy constructed by John Springford based on a basket of countries whose economic performance closely matched the UK’s before the Brexit referendum.[viii] The performance of the doppelgänger UK economy thus provides a counterfactual UK that did not leave the EU while nonetheless being exposed to the myriad shocks that impacted the world economy, including the Trump tariff war, the pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the ongoing technological shocks driving the digital transformation.

Compared to Springford’s doppelgänger-UK, Brexit-UK’s “…missed growth in goods and services trade account for about a £23 billion quarterly hit to UK exports, which is consistent with a GDP reduction of 4-5 percent compared to a Britain that had remained”.[ix] Plus, investment is way down compared to the pre-Brexit referendum trend.[x] Moreover, given the importance of the UK to the EU Single Market, investment in the EU has also fallen considerably. This is an important point for US policy considerations: undermining growth in your neighborhood is not good for your own longer-term growth. Further, as documented by the Tony Blair Institute,[xi] red tape for trading firms is way up, just as has been the case in the United States. The increased trade costs have driven many trading firms, primarily smaller ones, out of the trade.[xii]

The latter effect is particularly troubling for longer-term economic dynamism. Meredith Crowley, Oliver Exton and Lu Han estimate that “… in 2016, over 5300 exporters did not enter into exporting new products to the EU, whilst over 5400 exporters exited from exporting products to the EU. Entry (exit) in 2016 would have been 5.0% higher (6.1% lower) if firms exporting from the UK to the EU had not faced increased trade policy uncertainty after June 2016.”[xiii] While Rebecca Freeman and her colleagues do not identify a significant uncertainty effect (and conclude that “firms that have paid the sunk costs of exporting may prefer to wait until uncertainty is resolved before changing their relationships with foreign buyers and suppliers”), they agree that “the fall in EU exports is driven by smaller firms and that the effect is insignificant for the largest firms”; aggregating across firms, they estimate that Brexit reduced worldwide UK exports by 6.4% and worldwide imports by 3.1%, making the UK less open. And, yes, large numbers of small firms exited trade (about 16,400).[xiv]

Expect the Unexpected

Conventional ex-ante analysis of the Trump tariff proposal is consistent with actual experience in predicting significant negative impacts on the U.S. and partner economies.[xv] However, we cannot get directly from this limited history the full implications of the fundamental changes that are signaled by the America First Trade Policy.

The economic system is a complex, adaptive system that features many players, large and small, all responding to the changes that will be set in motion by U.S. tariffs and demands. They will act in their own interests in the absence of a pre-negotiated landing zone that avoids the lose-lose dynamics that can be set in train with defection from agreed rules and retaliation.

We have some experience with unilateral moves to make fundamental changes in international economic relations that involve tariffs and currency adjustments to protect domestic jobs and address inflation. On August 15, 1971, US President Richard Milhous Nixon announced “…a new economic policy for the United States.”[xvi] Its targets were problems related to unemployment, inflation, and “international speculation.” The centerpiece was the Job Development Act of 1971, a stimulus package to counter an economic slowdown and rising unemployment. A second measure targeted inflation; it involved a freeze on all prices and wages throughout the United States for a period of 90 days and the appointment of a Cost of Living Council to figure out how to achieve continued price and wage stability when the freeze ended. A third measure aimed to “protect the position of the American dollar as a pillar of monetary stability around the world.” It involved de-linking the dollar from gold and imposing a global 10% tariff on U.S. imports from all partners.

The outcomes of the Nixon Measures are a salutary lesson in what can go wrong with unilateral measures that lack adequate preparation.[xvii]

The negotiations for a restructured exchange rate system broke down, and a non-system emerged in which countries were free to adopt any exchange rate management framework they desired – except to peg their currencies to gold as was required under the Bretton Woods system that the Nixon Measures effectively terminated.

With the freeing up of exchange rates from the tightly managed Bretton Woods framework, financial markets jumped in: less than a year after the Nixon Measures, the Chicago Board of Trade introduced the world's first financial futures trading. None other than Milton Friedman rang the opening-day bell on May 16, 1972, to introduce futures trading in the British pound, Canadian dollar, Deutsche mark, Dutch guilder, Japanese yen, Mexican peso, and Swiss franc. The development of the massive financial derivatives market, the collapse of which resulted in the Great Recession of 2008/09, was off and running.[xviii]

While the Nixon Measures targeted price stability, within weeks of the devaluation of the US dollar against gold, OPEC responded by setting the price of oil in terms of gold. As the price of gold soared following the Nixon Measures, so did the price of oil, triggering the oil price shocks to the U.S. economy of the 1970s.[xix]

With the rise in oil price, the United States, as a net oil importer, saw its external merchandise trade account flip into deficit for the first time in the postwar era. At the same time, with the outbreak of volatility in commodity prices and currencies, the demand for international reserves for currency stabilization and liquid assets for private-sector hedging exploded. This translates directly into global demand for liquid US dollar-denominated balances for transactions, hedging, and store of value reasons by private foreign entities and for currency intervention by central banks. The world satisfies its demand by selling the United States goods and services and retaining the proceeds abroad as cash balances or U.S. Treasury Bills. By the same token, the United States runs a trade deficit as it buys more from the world than it sells to the world. We can immediately see, therefore, how the volatility induced by the Nixon Measures served to create the system that would lead to growing merchandise trade deficits, a development that is much decried by the new populist trade economics.[xx]

The Nixon Measures had also aimed to “protect the position of the American dollar as a pillar of monetary stability around the world.” But what happened was the opposite. The commodity price and currency volatility that emerged under the non-system that evolved following the Nixon Measures effectively injected “noise” into the international price system. This had the predictable effect: investing and lending mistakes were made and in due course banking and exchange rate crises – which were remarkably in hiatus during the Bretton Woods era[xxi] – returned with a vengeance. These would eventually take down whole continents: Africa and South America, both dominated by commodity production, suffered two lost decades, with knock-on political instability that led to failed states again and again. The world of international finance would become intimately acquainted with the Paris Club for sovereign debt restructuring, the London Club for private holdings of sovereign debt and Brady Bonds and other workarounds.[xxii]

The United States was not spared, the commodity price instability came home to roost in the form a surge in bank failures, including in the mutual savings bank sector, the commercial bank sector, and the savings and loan (S&L) sector at great cost to the U.S. public.[xxiii]

The Bottom Line

The populist trade economics that has influenced the framing of the America First Trade Policy is open to criticism on conventional grounds .[xxiv] The actual experience of attempting to implement it has not had the desired results – quite the opposite. Nonetheless, it has gained considerable influence, and a new chapter is set to unfold. What is even more troubling is that the biggest impacts may be changes that cannot even be realistically anticipated as starkly brought out by a prior instance where a fundamental change in global trade and monetary relations was initiated without a multilateral agreement in place, namely the Nixon Measures of 1971.

About the Author

Dan Ciuriak is Director and Principal, Ciuriak Consulting Inc. (Ottawa), Senior Fellow with the Centre for International Governance Innovation (Waterloo), Senior Fellow with the C.D. Howe Institute (Toronto), and Distinguished Fellow with the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (Vancouver). Previously, he had a 31-year career with Canada’s civil service, retiring as Deputy Chief Economist at the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT, now Global Affairs Canada) where he was responsible for economic analysis in support of trade negotiations and trade litigation and served as contributing editor of DFAIT’s Trade Policy Research series (2001-2007 & 2010 editions). He has written extensively on international trade and finance, innovation and industrial policy, and economic development, with particular focus on the digital transformation and the economic and technological roots of great power conflict.

[i] This section follows the analysis in Dan Ciuriak. 2025. “Misunderstanding America: A Journey Through Trade Economics with a Broken Compass,” Discussion Paper, 12 January. Available at SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=5094713.

[ii] Dan Ciuriak and Jingliang Xiao. 2018. “Quantifying the Impacts of the US Section 232 Steel and Aluminum Tariffs,” C.D. Howe Institute, Working Paper, June. Available on SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3190699

[iii] David Autor, Anne Beck, David Dorn & Gordon H. Hanson. 2024. “Help for the Heartland? The Employment and Electoral Effects of the Trump Tariffs in the United States,” NBER Working Paper 32082, January. https://www.nber.org/papers/w32082.

[iv] Alex Durante. 2024. “How the Section 232 Tariffs on Steel and Aluminum Harmed the Economy,” Tax Foundation Working Paper, May. https://taxfoundation.org/research/

[v] GAO. 2023. “Steel and Aluminum Tariffs: Agencies Should Ensure Section 232 Exclusion Requests Are Needed and Duties Are Paid,” General Accounting Office Report GAO-23-105148, 20 July. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105148

[vi] Martin Chorzempa, Mary E. Lovely, and Christine Wan. 2024. “The Rise of US Economic

Sanctions on China: Analysis of a New PIIE Dataset,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, Policy Brief 24-14, December. https://www.piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/2024/rise-us-economic-sanctions-china-analysis-new-piie-dataset

[vii] Lerner, Abba P. 1936. "The Symmetry Between Import and Export Taxes." Economica 3.11: 306-313.

[viii] John Springford. 2024. “Brexit, four years on: Answers to two trade paradoxes,” Insight, Centre for European Reform, 25 January. https://www.cer.eu/insights/brexit-four-years-answers-two-trade-paradoxes

[ix] Ibid.

[x] TBI. 2023. “Three Years On, Brexit Casts a Long Shadow Over the UK Economy,” Commentary 3 February, The Tony Blair Institute. https://institute.global/insights/geopolitics-and-security/three-years-brexit-casts-long-shadow-over-uk-economy

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] George Parker and Chris Giles. 2022. “The deafening silence over Brexit’s economic fallout,” The Financial Times, 20 June. https://www.ft.com/content/7a209a34-7d95-47aa-91b0-bf02d4214764

[xiii] Meredith A. Crowley, Oliver Exton and Lu Han. 2019. “Renegotiation of Trade Agreements and Firm Exporting Decisions: Evidence from the Impact of Brexit on UK Exports,” CEPR Discussion Paper No.13446,

[xiv] Freeman, Rebecca, Marco Garofalo, Enrico Longoni, Kalina Manova, Rebecca Mari, Thomas Prayer and Thomas Sampson. 2024. “Deep integration and trade: UK firms in the wake of Brexit,” Centre for Economic Performance Discussion Paper No. 2066, December. London School of Economics and Political Science. https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/dp2066.pdf

[xv] E.g., see, Warwick J. McKibbin and Marcus Noland. 2025. “Trump's threatened tariffs projected to damage economies of US, Canada, Mexico, and China,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, 17 January. https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2025/trumps-threatened-tariffs-projected-damage-economies-us-canada-mexico

[xvi] Nixon, Richard M. 1971. “Address to the Nation,” Office of the Federal Register (Ed.). Richard Nixon, containing the public messages, speeches and statements of the president - 1971. Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1972: 886-890.

[xvii] This analysis follows Dan Ciuriak. 2025. “The Consequences of the America First Trade Policy: What We Learn from the 1971 Nixon Measures,” Discussion Paper, 29 January. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=5116569

[xviii] For sources and a discussion, see Dan Ciuriak. 2013. "An Amicus Brief in the Economists' Court", Review of From Crisis to Crisis: The Global Financial System and Regulatory Failure by Ross P. Buckley & Douglas W. Arner, Canadian Business Law Journal 54(3), December 2013: 425-448.

[xix] The role of the pricing of oil in terms of gold in driving inflation is explicitly addressed in a study for the Federal Reserve Board. See: Michael Corbett. 2013. “Oil Shock of 1973–74”, Federal Reserve History, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/oil-shock-of-1973-74. Retrieved on September 4, 2024. See also, David Hammes and Douglas T. Wills. 2005. “Black Gold: The End of Bretton Woods and the Oil Price Shocks of the 1970s,” Independent Review 9(4), Spring: 501-511.

[xx] See, for example, the writing of Michael Pettis, including Michael Pettis. 2011. “An Exorbitant Burden: Why keeping the dollar as the world's reserve currency is a massive drag on the struggling U.S. economy,” Foreign Policy, 7 September. https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/09/07/an-exorbitant-burden/. Stephen Miran, the nominee to head President Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers has also written on this subject in the same vein. See: Stephen Miran. 2024. “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System,” Hudson Bay Capital, November.

https://www.hudsonbaycapital.com/

. For an extended discussion of the emerging populist trade economics, see Dan Ciuriak. 2024. “Populist Trade Economics and the Political Economy of Populism,” Commentary, 4 December. Available at SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=5043675

[xxi] Qian, Rong, Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2010. “On Graduation from Default, Inflation and Banking Crisis: Elusive or Illusion?” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 25(1): 1-36.

[xxii] See Dan Ciuriak. 2013. “An Amicus Brief”; note 18 for a detailed discussion.

[xxiii] For a documentation of the scale and costs of the bank failures, see Dan Ciuriak. 2013. “Canadian and US Financial Sector Stability Differences over Long History: Is There a Unifying Explanation?” Working Paper, available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2246150

[xxiv] See Dan Ciuriak. 2024. “Populist Trade Economics”, Note 20.